Quando il diritto di parola si trasforma in persecuzione

di Nancy Drew

(incipit in italiano e testo in inglese)

In questi giorni si ricorda il decimo anniversario dall’inizio della Rivoluzione tunisina – data che combacia con l’autoimmolazione del 26enne Tarek al-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, avvenuta il 17 dicembre 2010 a Sidi Bouzid, una cittadina non lontana da Sfax, porto dove attualmente partono i numerosi natanti di fortuna dei giovani tunisini che sperano di raggiungere Lampedusa.

La rivolta popolare, che scoppiò sull’esempio di ribellione del venditore ambulante – il quale si diede fuoco di fronte agli agenti di polizia che gli avevano requisito i pochi averi utili per la sopravvivenza – nel giro di un mese portò alla caduta della dittatura di Ben Alì (durata ben 23 anni) e accese la miccia per una ben più ampia contestazione popolare transnazionale, che giunse fin nella Repubblica Araba siriana – dove se ne vedono ancora i tragici segni – passando per Egitto e Libia e causando migliaia di vittime e arresti di massa.

Dopo dieci anni da quell’immenso atto, misto di coraggio e disperazione, compiuto da Mohamed Bouazizi, non si può affermare che la Tunisia abbia percorso strade puntualmente democratiche come era stato nei desideri espressi nelle piazze; anzi, dalle molte manifestazioni succedutesi negli ultimi periodi, e dagli scioperi generali indetti da numerose categorie professionali, la situazione pare sempre più impantanata in solchi di fanatismo religioso e di corruzione.

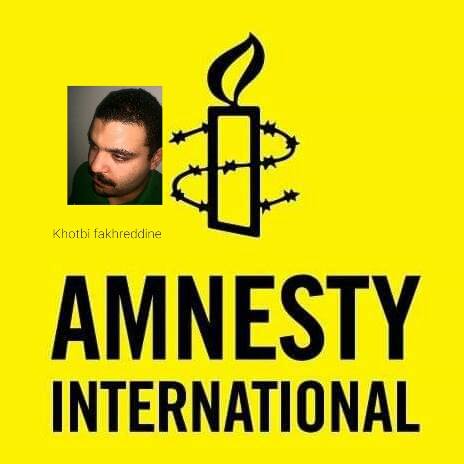

Per citare un esempio pratico, abbiamo posto alcune domande a Fakhreddine al Khotbi, un giornalista radiofonico 28enne che, dopo aver denunciato un giro di corruzione nella bellissima Tozeur – città della Tunisia meridionale, famosa per le sue mura di terra color del deserto – è stato costretto a lasciare il lavoro, ed è diventato il protagonista di un caso di persecuzione politica, di cui si occupa anche Amnesty International.

You are a journalist. How long have you been carrying on your profession?

FAK: «My work as a journalist started in 2016. I am a reporter and a radio journalist».

Did you work in a local magazine/station or in a national radio?

FAK: «My job was as a radio reporter at a local radio station in Tozeur, in southwestern Tunisia. The radio station was called Djerid Fm. That was my regular job. Besides, I was active as a blogger on Facebook under the name of Fakreddine al Khobti/فخر الدين الخطبي ».

What were your articles about? Politics, foreign countries, economics?

FAK: «My articles were generally local and concerned news about the city of Tozeur. In particular, I liked to dwell on the positive sides of the issues, rather than the criticisms. I did not have specific addresses regarding the topics, which were all local news – such as protests, or goals to be achieved or already achieved. Daily news. A topic that I felt particularly mine was the violation of human rights in Tunisia and Tozeur. As a matter of fact, I was also a member of Amnesty International and worked in a group based in my city».

Why did you have to leave the journalistic profession? FAK: «I was forced to do it under strong pressure from the Tunisian authorities. It was them who wanted me to leave my work on the radio».

You claim to be persecuted by the police or by criminals on behalf of corrupt politicians. In what way? Why are you harassed? FAK: «It all started with exposing some allegations of corruption, mainly in the agricultural sector, and shedding light on the behavior of some leaders of my city. After that, under strong psychological pressure, I was forced to leave my job. Not even the radio station where I worked did stay by my side. I have been psychologically and physically injured several times, although officially there are no charges against me for any crime. I don’t know how to defend myself and it seems to me that I have lost all dignity. People, (probably) belonging to the corruption ring, turn the authorities against me. I am forced to live without a job; so, in addition to the harassment, I am also unemployed and without economic incomes. They also push some people to hurt and insult me. I was beaten with a stick on the head almost to death. I

You claim to be persecuted by the police or by criminals on behalf of corrupt politicians. In what way? Why are you harassed? FAK: «It all started with exposing some allegations of corruption, mainly in the agricultural sector, and shedding light on the behavior of some leaders of my city. After that, under strong psychological pressure, I was forced to leave my job. Not even the radio station where I worked did stay by my side. I have been psychologically and physically injured several times, although officially there are no charges against me for any crime. I don’t know how to defend myself and it seems to me that I have lost all dignity. People, (probably) belonging to the corruption ring, turn the authorities against me. I am forced to live without a job; so, in addition to the harassment, I am also unemployed and without an income. They also push some people to hurt and insult me. I was beaten with a stick on the head almost to death. I’m still alive – saved by a God’s miracle. Apart from that, I had a hand broken. All that led to many health issues. I have lost my dignity and I feel like a rightless citizen. I have been tortured without any charge, and those who persecute me are true professionals in doing so, including hiding all evidence and threatening witnesses. Despite quitting my job as a radio journalist, they haven’t forgotten me, that’s why I’m still being watched. They don’t have any right to hurt me under Tunisian law; but there are some senior officials of the Tunisian Ministry of Interior who can persecute and even kill people and no one can stand up to them. Unfortunately, some ‘roots’ of the Ben Ali regime and of his dictatorship are still there».

You were an activist for Amnesty International in Tunisia. So, you were also fighting for human rights. Are human and civil rights respected in Tunisia?

FAK: «Yes, I was an Amnesty International activist but this is really dangerous. They can do anything to hurt you. I was an active member of Tunisian Amnesty International in Tozeur and I have reported some local cases of human rights violations. The problem in Tunisia is that the law protects citizens only in theory, but in practice they could even be killed by policemen without anyone daring to mention the case – unless relatives or families are rich and important. All the others, the poorest, could be buried alive without anyone saying a word».

How is your life now? Do you have a family and/or children?

FAK: «No, I haven’t married yet, because I am out of work; unfortunately, I cannot afford to feed a wife and children. And, apart from that, my situation is quite dangerous».

Are there any reasons to think that the members of your family could be at risk?

FAK: «Yes. Usually, they focus on the specific person, but they can hurt or act against your family as well, if they want».

What do you want to say to Italian and international readers about what’s happening to you, and problably to other Tunisian journalists and activists?

FAK: «It would be very important if they publicized and sympathized with my case – which is well known all over the world and supported by Amnesty International. If you write my name on Google (Fakhreddine al Khotbi) you’ll find it out. A case of persecution and suffering that has lasted for three years and shows no solution. Tunisia is a beautiful country but its rulers are still far from being democrats. Democracy, human rights and freedom of speech are still utopias».

Sabato, 26 dicembre 2020

In copertina: Manifestazione di protesta dei giornalisti tunisini.